Surfing Gravitational Waves

Science to ride gravitational waves

By Jonathan Amos BBC News science reporter, Hanover

Many expect it to be one of the biggest scientific breakthroughs of our age: "There'll certainly be a Nobel Prize in it for somebody," says Jim Hough.

The UK professor is standing on a farm road in Lower Saxony, Germany, with a crop of beet on one side and sprouts on the other.

But the real interest lies at his feet - with some shabby, corrugated metal sheeting. For a moment, it looks like an upturned pig trough until you realise it stretches for hundreds of metres.

The sheeting hides a trench and, within it, the vacuumed tube of an experiment Hough believes will finally detect the most elusive of astrophysical phenomena - gravitational waves.

The Glasgow University scientist has been chasing these "ripples" in space-time for more than 30 years and feels certain he is now just a matter of months away from bagging his quarry.

"It will be a big event for two reasons: it will be yet another confirmation that Einstein's Theory of General Relativity is correct, but it will also open up a new kind of astronomy that will allow us to look inside the most violent events in the Universe."

A new kind of astronomy requires a new type of "telescope", and that's just what Hough and UK-German colleagues have been developing on farmland a short drive from Hanover. It is called GEO 600.

Stretch and squash

Its looks are deceptive. Anonymous silver shacks house state-of-the-art electronics and a high-power laser.

And then there is that trench - two in fact, running out at right-angles to each other for more than half a km. Their vacuum tubes end in super-smooth mirrors slung by pure-glass wires from damped frames.

This is precision engineering at the extreme. To have any hope of detecting gravitational waves, it has to be.

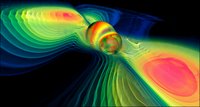

Unlike electromagnetic waves - the light seen by traditional telescopes - gravitational waves are extremely weak. If one were to pass through your body it would alternately stretch your space in one dimension while squashing it in another - but the changes are fantastically small.

Any moving mass will send gravitational waves radiating outwards at the speed of light; but only truly massive bodies, such as exploding stars and coalescing neutron stars, can disturb space-time sufficiently for our technology to pick up the signal.

"The displacement sensitivity of GEO 600 is one three-thousandth of the diameter of a proton," explains Professor Karsten Danzmann, from the Albert Einstein Institute and Hanover University.

"Put another way, it's equivalent to measuring a change of one hydrogen atom diameter in the distance from the Earth to the Sun."

And it is these tiny deviations that GEO 600 hopes to measure in the laser light it bounces through its L-shaped tubes.

Cosmic symphony

Careful refinement and tuning of the instrumentation has moved the installation very close to the required sensitivity - towards a possible "eureka" moment.

The UK-German team is working with US colleagues who have two similar facilities known collectively as Ligo - Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory.

These set-ups, at Livingston in Louisiana and Hanford in Washington, employ laser arms that are 4km long.

Both Ligo and GEO 600 are to begin a full "science run" in November, with the aim of gathering data continuously for 18 months. In that time, they would expect to see perhaps two events, maybe more, that can be put down to a passing gravitational wave.

A detection would be confirmed if at least two of the widely separated installations record the same signal. But, as great an achievement as that would be, it really is just the start.

The real aim is to have a new means of studying the Universe - to trace its exotic phenomena in detail in a way that does not rely on light.

"The analogy I like is this: imagine being able to see the world but you are deaf, and then suddenly someone gives you the ability to hear things as well - you get an extra dimension of perception," explains Professor Bernard Schutz from the Albert Einstein Institute and Cardiff University.

"Up until now we've only been able to see the Universe with our telescopes, but with gravitational waves we will be able to hear it as well; and that's going to convey a different type of information.

"Most of the Universe cannot emit electromagnetic waves - we will never see it with light. But we can see it, or parts of it, with gravitational waves."

With this in mind, the scientists have even grander plans which go beyond merely upgrading GEO 600 and Ligo: they want to put an observatory in space.

Preparations for this mission, known as Lisa (Laser Interferometer Space Antenna), are well advanced. It would fire lasers between three spacecraft flying in formation and separated by five million km.

Lisa would allow scientists to look at lower frequencies than are possible on Earth, to signals that come from the merger of monster black holes.

Modelling also suggests it should be capable of detecting remnant radiation from the Big Bang itself, enabling science to probe the first moments of creation and perhaps pull together some of its contradictory theories.

"You don't often get things that are very small that are also very massive but, of course, in the very earliest moments of the Universe we did," says Professor Mike Cruise from Birmingham University.

"Some of these observations are going to give us a clue as to how gravity can be viewed in terms of quantum mechanics and the prospect of that is just mind-boggling."

BBC Science

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home